Generative Models hate this one trick to mitigate Observation Complexity

Abstract

The “Generative Model” is often defined as a Neural Network (NN) that allows for the querying of some input and receiving some output. In the case of a Generative Observation Model, it defines $p\left(o \, \mid \, h_t\right)$. To those with a keen eye, you might realize that this begets modeling every pixel, shadow, and irrelevant texture in the case of a visual observation. Discriminative Particle Filter Reinforcement Learning (DPFRL) for Complex Partial Observations says “why bother?” and instead proposes the idea of using a set of learned latent states and weights to approximate the belief. By matching particles to observations and scoring them, DPFRL instead skips the need for messy reconstructions. Add on these magical “Moment Generating Functions” (MGFs) and we have a system better equipped to handle visually complex environments.

Generative Models Just Can’t Cut It

A Generative Model (in the case of Reinforcement Learning) is typically a Neural Net (NN) that defines the probability of seeing a specific observation given some latent state: $p\left(o \, \mid \, h_t\right)$. These generative models must essentially model every variation of every feature for every environment. In the case of an image, this means considering every pixel, even if said pixel contains irrelevant data. This yields what is called a “Complex Observation Environment”.

Generative Models have difficulty with this as they inherently consider these irrelevant visual complexities. They’re like me in the Lego store, unable to resist purchasing something. While a generative model may do fine in an environment similar to the one that it was trained in; turn the lights off and you might suddenly find your algorithm struggling to perform just as well. This is because the agent receives an observation (while possibly of an environment that it has seen before) that it perceives as different due to the different pixel values or latent state reconstruction. Imagine if, upon turning the lights off in your house, you suddenly believed you were in a completely different country. That would probably make you act differently than you would if you realized you were still in your house.

This leads to a desire for some Observation Model that is more capable of ignoring these irrelevant details. What would this observation model look like, however? If we consider ourselves as a little soldier that needs to localize itself; using a generative model is like knowing (or having to know) every possible environment under every possible circumstance and then get a probability distribution of where it is with such knowledge. This is understandably unreasonable, so what if we instead just looked at features of the environment we are in and made a guess from there.

Today’s Hero: The Discriminative Particle Filter

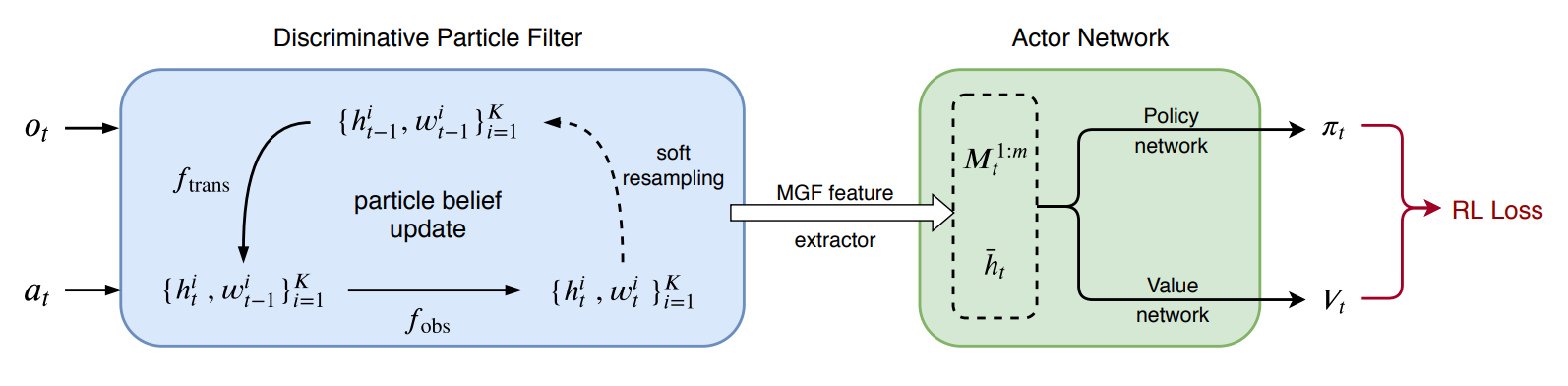

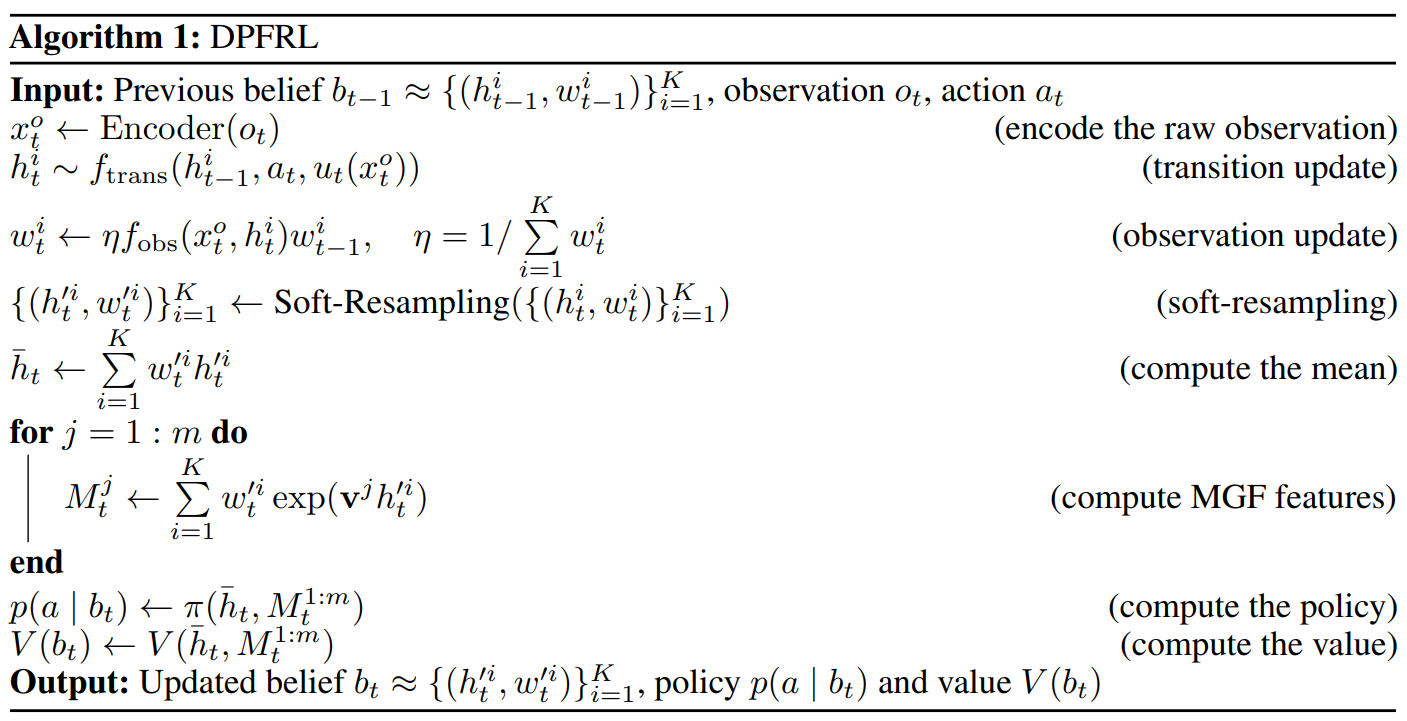

The authors of Discriminative Particle Filter Reinforcement Learning (DPFRL) propose the discriminative belief update. A discriminative update “discriminates” by which particle better fits the current observation. This is done by the use of two learned NNs trained end-to-end.

The first network is an Observation-Conditioned Transition Function $h_t^i \sim f_{trans}\left(h_{t - 1}^i, a_t, o_t\right)$. This network outputs / proposes a new latent state that it believes is most likely given the previous latent state, current action taken and observation currently seen. Back to our little soldier analogy; this is like the soldier considering what it sees and guessing where it could be. Is it a really green or lush environment? Perhaps it’s in a soil-rich ecosystem or near water? Is it really rocky and dry? Perhaps it’s at altitude or in a hot environment? This is what the observation conditioned transition function does. It considers its environment (and its previously guessed location, as well as what action it just took) and guesses where it is.

The second network is a Compatibility Function $f_{obs}\left(h_t^i, o_t\right)$. The previous “proposed new latent state” is then assigned a weight by $f_{obs}$ given said latent state and current observation (multiplied by the previous weight and scaling factor $\eta$). Again, back to the little soldier analogy; this is like saying “Ok, I think I’m here now… does that actually align with what I’m seeing?”

Consider the following example: Our little soldier is in an icy, cold environment with penguins everywhere. The soldier sails North and reaches a semi-lush / arid environment with kangaroos. The transition function $f_{trans}\left(h_{t - 1}^i, a_t, o_t\right)$ takes into account that the soldier moved North, was previously somewhere cold and icy and is now seeing someplace arid. It then proposes a set of new locations (latent state particles), let’s say: [Southern Africa, Southern South America, Southern Australia]. The compatibility function $f_{obs}\left(h_t^i, o_t\right)$ then weights each of these proposed latent state particles according to what it is seeing. It sees a semi-lush / arid environment so perhaps it could be any of the three, but the kangaroos align with a high weight for Southern Australia. Thus, each latent state has weights perhaps as such: {{Southern Africa, 0.2}, {Southern South America, 0.1}, {Southern Australia, 0.7}}. This set of latent states and associated weights define our set of particles.

In the last Discriminative Particle Filter step, our particles are regenerated (as is common in particle filters) to prevent particle degeneration. The unnormalized particle weights found from the compatibility function are normalized, and these particles are passed back into the filter to be used again for the next step. The former two steps are wrapped into a “Soft-Resampling” step as called by the original authors. The final step is to form our particles into a belief used for our policy and value updates.

Policy & Value Update

The policy update step is separated into two routines: the belief formulation and policy and value updates. The belief is formulated using the mean latent state $\left(\bar{h}_t\right)$ and Moment Generating Function (MGF) features. These MGF features summarize the belief by evaluating the weighted latent states at learned locations, capturing higher-order information. This higher-order information is more descriptive than just the mean, which is useful in complex environments.

This is like our little soldier considering all particles (proposed locations), picking a final value (mean) and extracting high-order features from the set of all of them (such as flora and / or fauna in each proposed location) to make a final decision about where it is (its belief).

These features combine to form a permutation-invariant belief vector $\left[\bar{h}_t, M_t^{1:m}\right]$. This belief vector is then used to determine our policy $\pi\left(a_t \, \mid \, b_t\right)$ and value $V\left(b_t\right)$.

So… Why Does This Work?

The short version is that DPFRL optimizes for complex environments, not reconstruction; it only learns to recognize observation features that help pick good actions. The Observation-Conditioned Transition Function $f_{trans}\left(h_{t - 1}^i, a_t, o_t\right)$ steers particles toward latent states that can actually explain what was just seen considering the agent dynamics. The Compatibility Function $f_{obs}\left(h_t^i, o_t\right)$ assigns unnormalized scores to the latent state particles relative to its learned ranking. These scores are normalized along with particle regeneration during a Soft-Resampling step.

DPFRL cleverly turns the problem of modeling the full image distribution $p\left(o \, \mid \, h_t\right)$ into an easier one: learn to propose plausible hypotheses from what you just saw and score them for decision relevance. On benchmarks where observations are visually complex, DPFRL maintains “state-of-the-art” scores while baselines using a generative model struggle as they see observations of the same environment under different conditions as completely different environments.

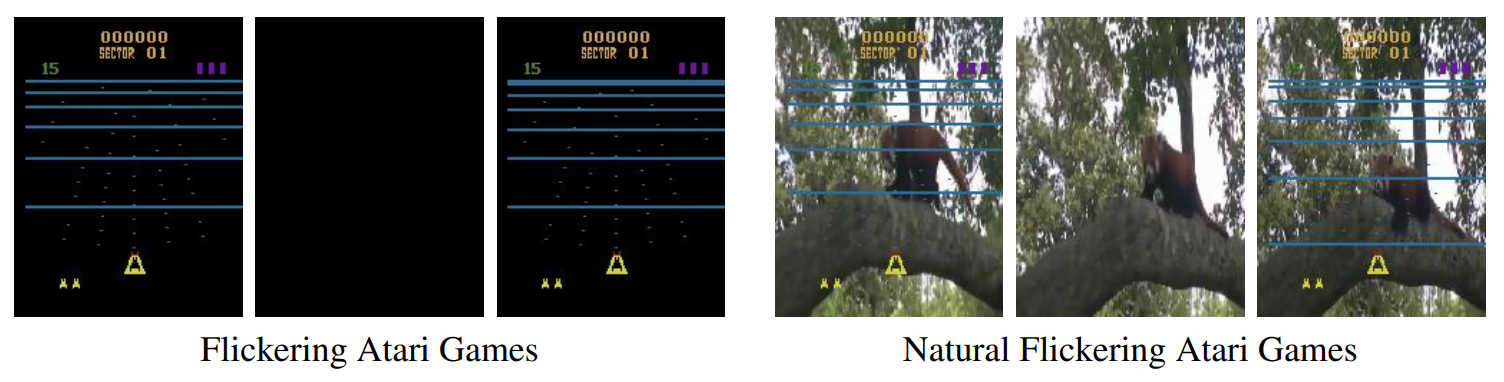

DPFRL only needs to learn “does this particle match what I’m seeing for decision purposes?” instead of “can I reconstruct every pixel, including that coffee stain?”; a way easier problem to solve. On benchmarks like Flickering Atari Games (where frames randomly go blank) and Natural Flickering Atari Games (the same as the prior except with random YouTube videos as backgrounds), DPFRL substantially outperforms methods using generative models. TL;DR: Instead of painting a masterpiece to prove you’re in a museum, just check if the important features of what you see match “you’re in a museum”.

FAQ

I don’t like tuning hyperparameters… How many knobs does DPFRL have to tune?

Not many actually!

- Particle count $K$: more increases compute and memory usage, but better handles multi-modality and approximates of the posterior distribution.

- Soft‑Resampling $\alpha$: higher leads to importance sampling; lower leads to more exploration to avoid particle collapse.

- MGF feature count $m$: captures more higher-order information from the particle moments.

What are the trade‑offs?

You don’t get the additional reconstruction signal that some generative models can use, which sometimes helps supplement learning in simpler settings. Similarly, with too few particles or extremely complex visuals, the model can still struggle to maintain a sharp belief.

What are MGF features in plain English?

Think of them as quick “probes” of the belief that capture not just the average guess, but also how spread out or lopsided the guesses are.

What if my observations are simple?

The performance gap narrows; generative models, mean‑only belief summaries, only 1 particle and more may perform similarly, but DPFRL remains a solid, structured baseline comparable to generative models nonetheless.

Resources

Considering looking into DPFRL for your use case? Perhaps you want to learn about specific algorithmic implementation details to further your understanding of the high-level topics. Here’s a list of nice resources for you that I found useful:

Original paper: Discriminative Particle Filter Reinforcement Learning (DPFRL) for Complex Partial Observations Author GitHub implementation: DPFRL