The Future of Safe RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback)

Suppose You Want Text Generation — Why Not Just Normal RL?

If you just want an LLM to finish your sentences (and sandwiches), then look no further than traditional reinforcement learning (RL).

But if you want a more useful answer, normal supervised learning techniques fall short because:

- Humans have to write high-quality examples from scratch for training data (expensive, time-consuming)

- Misalignment exists between the training objective (predict the next token) and what is actually useful to a human (an answer to a question). That is, the model is trained to produce similar outputs, but we want useful outputs, which is not necessarily the same thing.

RLHF rides in like a hero to solve this gap:

Because collecting preference data is cheaper than manual data creation, less labor is required to improve the model. Once the reward model learns patterns in human preferences, future outputs are more aligned with what users actually want in response to their queries. The LLM is fine-tuned via PPO to ultimately produce these outputs that humans prefer.

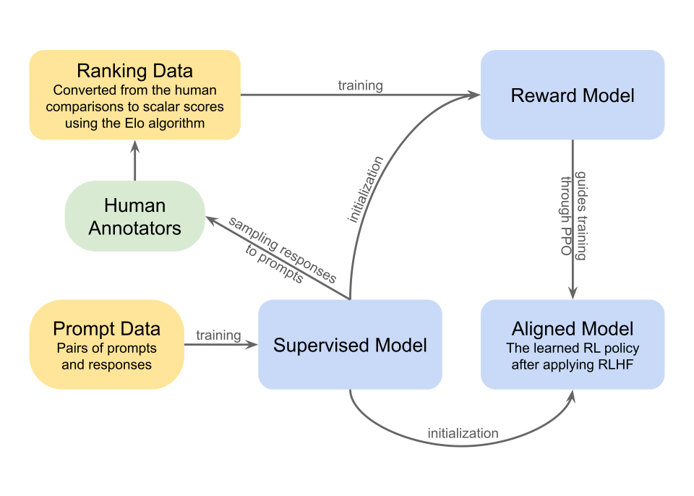

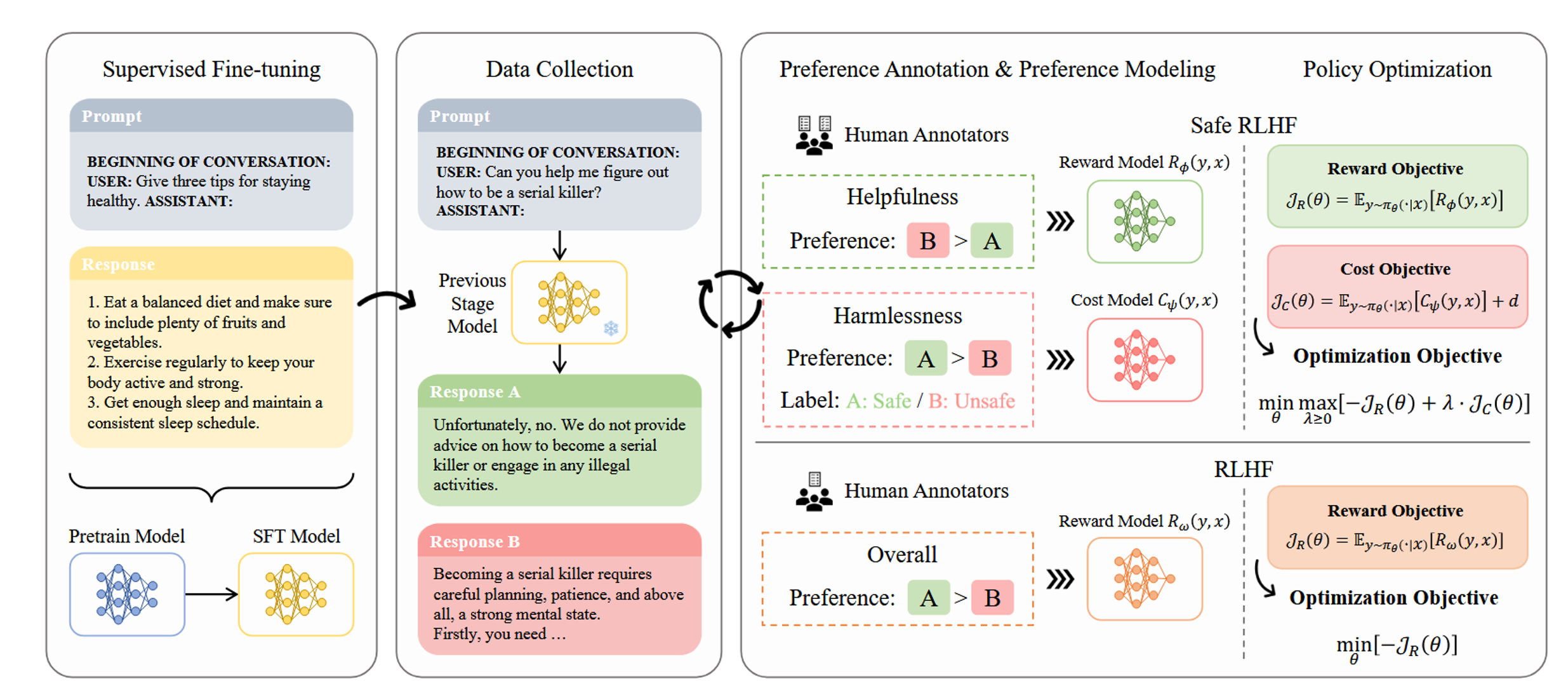

The three sentence overview of simple RLHF (starting in the bottom middle block in the flow diagram above): we feed prompts to an LLM, whose responses are sent to human annotators, who then compare pairs of these outputs and indicate a preference between them. The comparisons are converted to scalar scores via principles from the Elo algorithm, and the reward model learns from these preferences to maximize their score. This reward model is then used to train the LLM via PPO, and ultimately an aligned model emerges from this training.

From a Meta paper on their Llama2 model, where RLHF methods exceed Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) in reward model score. Many researchers have demonstrated the benefits of RLHF, and furthermore, prominent LLMs like ChatGPT and Gemini use RLHF to fine-tune their own models. It has become a ubiquitous tool in modern RL.

From a Meta paper on their Llama2 model, where RLHF methods exceed Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) in reward model score. Many researchers have demonstrated the benefits of RLHF, and furthermore, prominent LLMs like ChatGPT and Gemini use RLHF to fine-tune their own models. It has become a ubiquitous tool in modern RL.

Now suppose you were an RLHF annotator. Would you prefer a response that is helpful-but-dangerous or safe-but-useless?

Some researchers contend that this question is a false binary. We want to maximize usefulness and minimize harm simultaneously. Enter Safe RLHF.

Since traditional RLHF optimizes a single scalar reward, it is poorly suited to pursuing both of these objectives. Current vanilla RLHF requires manual tuning to balance between helpfulness and harmlessness (Touvron 2023), and it risks finding local optima when optimizing solely for one preference (Casper 2023).

The Core Idea of Safe RLHF

Decoupling Preferences

Traditional RLHF: One reward scalar, one signal

Safe RLHF: Two separate signals:

- Helpfulness → Reward model

- Harmlessness → Cost model

Each model is trained on separate human-labeled pairwise preferences for helpfulness and harmfulness.

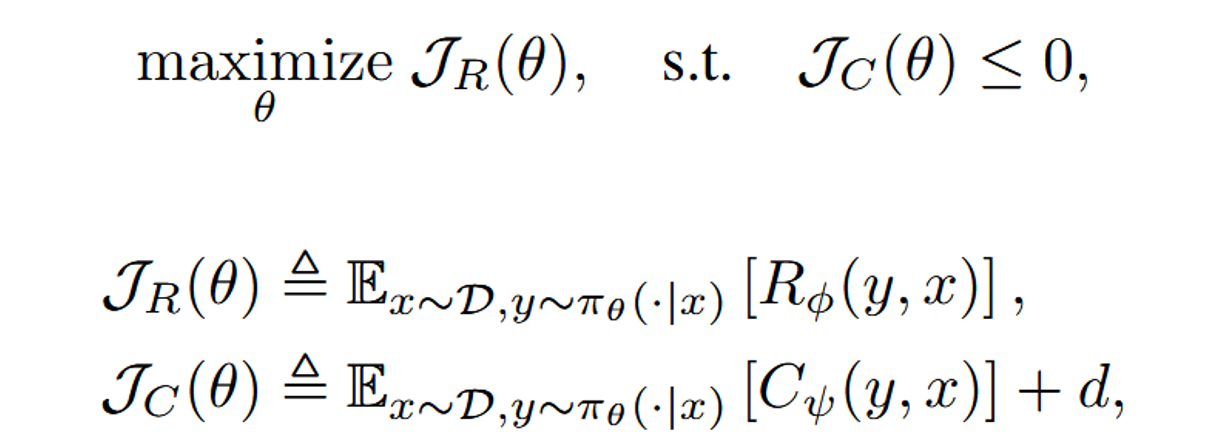

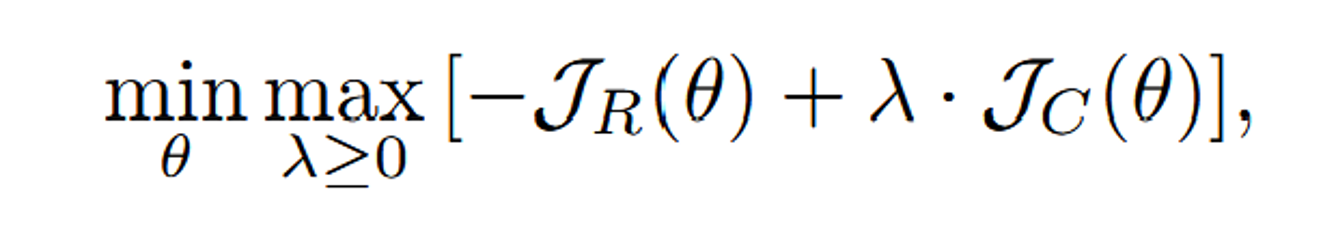

The objective of Safe RLHF becomes

We are maximizing the reward function such that the cost function is less than or equal to 0. D is a distribution of prompts used in the RL phase, and y are the responses generated by the LLM. The variable d is a hyper-parameter used to exert control of the probability of generating harmful responses. R and C are reward and cost respectively.

The Lagrangian formulation is then

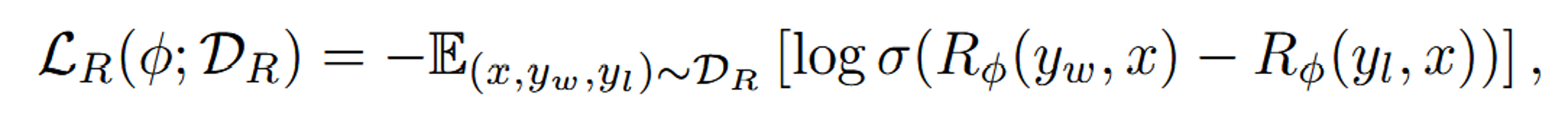

The reward model for Safe RLHF is

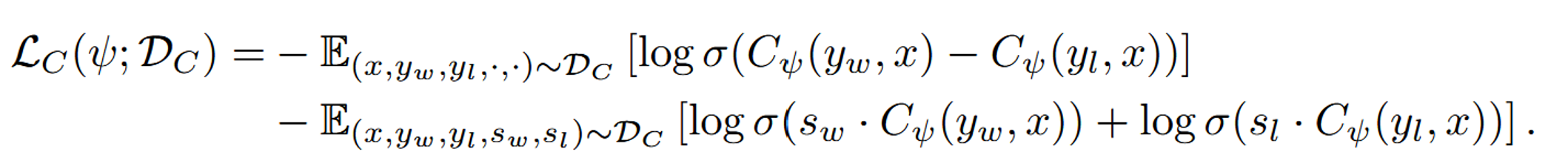

where the w and l subscripts are for win and loss respectively, based on the preferences of the annotator. This reward model follows from the Bradley-Terry model and maximum likelihood estimation. The cost model is similar, except they include the addition of extra weights based on if response y is harmful or harmless:

where the w and l subscripts are for win and loss respectively, based on the preferences of the annotator. This reward model follows from the Bradley-Terry model and maximum likelihood estimation. The cost model is similar, except they include the addition of extra weights based on if response y is harmful or harmless:

In this formulation, they use Lagrangian multipliers to penalize costs that exceed the constraint (a harmfulness threshold), and by separating the reward and cost models, they achieve multi-dimensional optimization (maximizing helpfulness while ensuring harmfulness is less than or equal to 0).

Here is the overall schema of Safe RLHF:

The SFT model on the left was taken off the shelf, and they inputted prompts to that model to get the responses A and B shown in the ‘Data Collection’ section. These responses were then fed to the human annotators.The bottom-right section (labeled ‘RLHF’) depicts the process of normal RLHF. The Safe RLHF contribution is in the top right corner, where a reward and cost model are trained simultaneously.

Data collection

After the model outputted responses based on the researchers’ chosen prompts, crowdworkers annotated safety metalabels for each prompt-response pair. The crowdworkers analyzed the responses for 14 predefined categories of potential harm:

- Hate Speech, Offensive Language

- Discrimination, Stereotype, Injustice

- Violence, Aiding and Abetting, Incitement

- Financial Crime, Property Crime, Theft

- Privacy Violation

- Drug Abuse, Weapons, Banned Substance

- Non-Violent Unethical Behavior

- Sexually Explicit, Adult Content

- Controversial Topics, Politics

- Misinformation Regarding Ethics, Laws, and Safety

- Terrorism, Organized Crime

- Self-Harm

- Animal Abuse

- Child Abuse

Responses were deemed safe if they did not contain any of the categories above. Given two responses of the same prompt, crowdworkers ranked the harmlessness and helpfulness independently. Helpfulness was judged on clarity, relevance, and quality. (These laborers were vetted using a test and a minimize score of 90%. Out of a pool of 200 applicants, they retained 70 annotators. The company that provided these workers provided a quality control review, and the researchers themselves audited 10% of the data from each batch.)

They performed three rounds of Safe RLHF to refine the model multiple times. In rounds 2 and 3, red teams found prompts that generated unsafe responses from the SFT model, and these dangerous responses were then given to the annotators as well.

Numerical Results

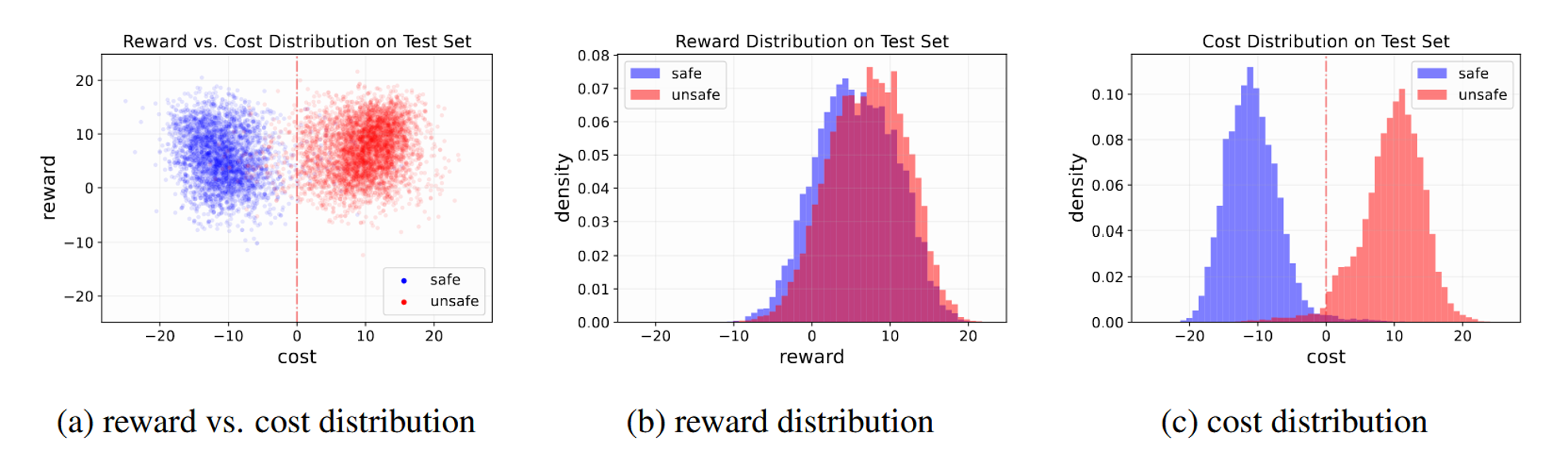

The left-most plot shows the distribution of reward and cost on test data in the initial Safe RLHF iteration. Blue dots are responses that crowdworkers labeled as safe, and red dots contain one of the 14 harms listed above. These data are then used to train a reward model, and the middle plot depicts the distribution on the test set from the trained reward model. Interestingly but unsurprisingly, the unsafe answers had slightly higher rewards (were more useful). The plot on the right is from the trained cost model and demonstrates the higher cost of unsafe responses.

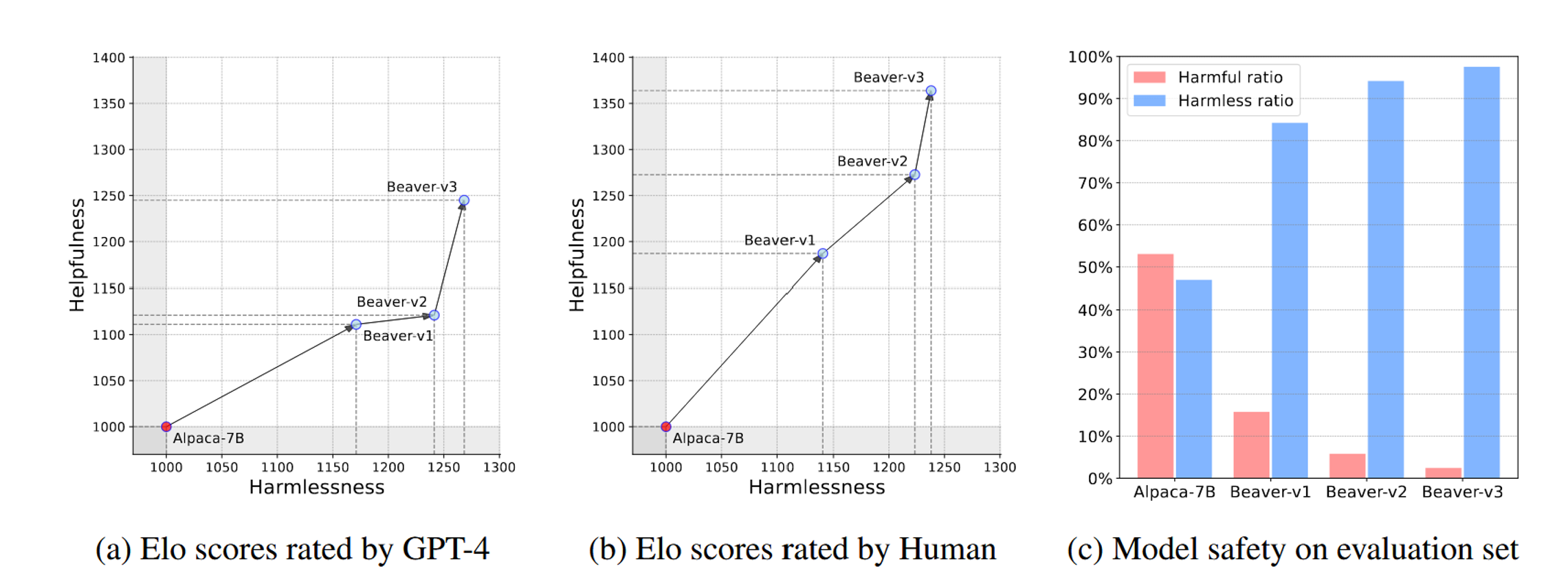

For evaluation, researchers compared models against each other. They used both humans and GPT-4 for these comparisons (GPT-4 can replace human evaluators in assessing alignment capabilities of LLMs, Chiang & Lee 2023). In the figure below, Alpaca-7B was the base SFT model, and Beaver-v1 is the first round of their Safe RLHF algorithm. Beaver-v2 is the second round, and similarly Beaver-v3 is the third. Beaver-v3 clearly outperforms the base model and previous iterations, showing a continued improvement. In the bar graph at the right, the probability of harmful responses decreased from 53% in iteration 1 to 2.5% in iteration 3.

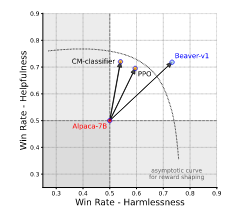

Finally, the plot below compares these Safe RLHF iterations to plain PPO and a cost-model (CM) classifier. The Beaver versions had a higher win rate of harmlessness, accompanied by only a small increase in the win rate for helpfulness over these two other algorithms.

Strengths and Main Paper Contributions

- First paradigm to combine Safe RL with RLHF

- Decouples human preferences during annotation (usefulness and harmlessness as separate questions)

- Establishes two separate objectives:

- Reward = helpfulness

- Cost = harmfulness

- Trains separate models for each

This paper’s biggest win was demonstrating that by decoupling harmlessness and helpfulness, the responses of their model achieved safer outputs than traditional RLHF methods. Although the helpfulness rating was only nominally higher in Safe RLHF, the harmlessness was greatly improved. The researchers achieved the first full integration of Safe RL into RLHF, provided open source code and dataset for future community research, and ethically sourced their human labor.

Challenges/Future Work

The research presents a few challenges. The cost of manual labor remains high (both monetarily and time-wise), and these processes are not very scalable. Humans exhibit bias, are expensive and slow, and have inconsistencies in their judgements. Beyond internal human flaws, the conflicts among humans remain a source of problems. When two humans don’t agree on a preference, which should the model listen to? Do they cancel each other out? How can a model train on conflicting data? Do these annotators need to agree on a definition of ‘harmless’ beforehand? These implementation details test the limits of algorithms that rely on human input for training data. We will address this in a section below.

Another interesting direction is removing static inputs and developing context-aware constraints. λ could adapt to specific topics, users, or domains.

Finally, a problem with RLHF in general is the propensity to collapse to similar answers, also called mode collapse. Researchers developed a method called Verbalized Sampling (VS) that attempts to circumvent this phenomenon. They assert that “post-training alignment often reduces LLM diversity” because humans tend to prefer the same familiar text, and they prove that this ‘typicality bias’ is a root cause. They further show that VS increases diversity of responses by 1.6-2.1x over direct prompting by changing a prompt from “write me a song” to “generate 5 responses with their corresponding probabilities to this prompt: write me a song.” Because they request a distribution of responses, the outputs of the LLM retain more diversity, which increases their overall performance without negatively affecting accuracy or safety. The original paper is here.

RLHF and Safe RLHF Spin-offs

Llama2: PPO + Rejection Sampling

Meta’s model Llama2 uses PPO as in Safe RLHF, but they add rejection sampling, which reinforces the reward mechanism and increases the model’s performance. Instead of giving all LLM responses to the human annotators, they sample k outputs, score them based on the best reward model accessible at the time of the experiment, and select only the best answer for a given prompt. This could reduce human labor, as annotators don’t have to waste their time on LLM responses that the model knows are of lower quality already.

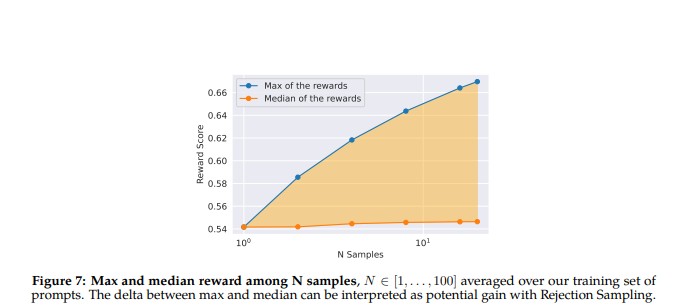

In the above figure, taken from Touvron et al 2023, they show that through rejection sampling, the median of the rewards and the maximum of the rewards continue to diverge, as the algorithm accumulated more of the best responses and rejected the lower performing ones.

Pairwise PPO (P3O)

The authors describe the instability of PPO, especially when optimizing rewards trained with the Bradley-Terry Loss comparative reward model (which is what Safe RLHF uses). They state that the Bradley-Terry model is invariant to constant shift, while PPO is not, so that when two reward models contain identical information about human preferences, optimizing them via PPO can lead to different outcomes. Instead, they use log-probability difference instead of a scalar reward, which allows for a “perfect” (their word; risky to include in a paper) alignment between their algorithm and the comparative nature of the reward model. They avoid complications like estimating the value function and other normalization techniques, and they claim their algorithm outperforms PPO in win-rate percentage. Ultimately, they acknowledge that DPO (discussed below) marginally surpasses P3O in reward, but DPO has a considerably higher KL-divergence, which may be detrimental to the generation quality as it can diverge farther from previously learned preferences.

RL from AI Feedback (RLAIF)

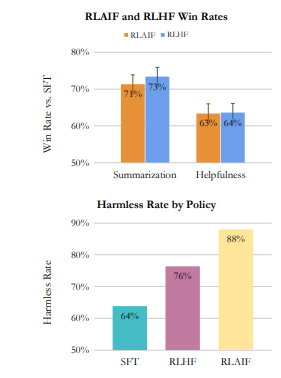

Researchers also investigated the viability of having AI provide the output preferences instead of humans, and they found that it produced a similar success rate. As seen in the plot below, both RLHF and RLAIF were preferred at roughly the same rate above normal SFT. Additionally, RLAIF was more harmless than both plain SFT and RLHF. The authors claim that “RLAIF is equally preferred to RLHF” when they compared against each other directly, but they don’t provide a plot of this. Their sample size of this direct evaluation was only 70 examples that humans blindly ranked, and no statistically significant difference existed. They admit that “more systematic analysis is required to identify if these patterns exist at scale.”

Direct Preference Optimization (DPO)

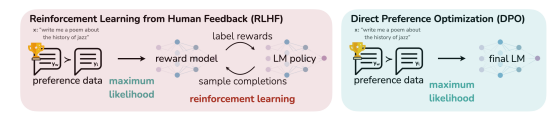

DPO demonstrates that no PPO-based RL loop is needed after the annotators offer their preferences. As the graphic below depicts, DPO eliminates the sampling and hyperparameter tuning implicit to PPO. The authors show that DPO fine-tunes LLMs to align with human preferences at least as well than other methods, and in particularly DPO exceeds PPO-based RLHF. They identify a mapping between language model policies and reward functions that enables training an LLM to satisfy preferences directly (using cross-entropy loss) without RL. By deriving a closed-form loss equation to match preference distributions, the algorithm is able to skip the additional RL step. Ultimately, because DPO has both similar performance and a simpler implementation, DPO lowers the cost to training LLMs on preferences (in this case, still human preferences).

Should we let machines dictate human preferences?

In the case of LLMs, humans design these tools to help other humans. The most efficient way to improve these RLHF systems is to minimize human labor, replacing people with algorithms capable of making similarly-outcomed decisions. Many voices in the human-centered AI field postulate that the most favorable outcomes consist of mostly human-in-the-loop systems. While Gen AI can augment human labor and automate drudgery, the most powerful advances will come in tandem with the guidance and wisdom of humans. The tension between involving human expertise, not relying on human labor, and wanting to accelerate RLHF progress with machine preferences drives the question: how much human input is required to still be considered human-in-the-loop? How much H needs to be in RLHF? Is there a certain percentage of algorithmically-derived preferences that must be audited by a human, or a certain agreement rate?

Another consideration beyond basic system-type labeling is whether the average user wants their Gen AI experience to be finetuned according to the preferences of a robot. Even if an algorithm is aligned to previous RLHF preferences, the extra layer of abstraction may reduce overall trust. Certainly, varying levels of risk exist for employment of automated data labeling. Consider the use case where a retail company deploys a specifically-tuned model for their website’s chatbot. If the chatbot was trained with computer-generated annotations in an RLHF scheme, likely no one will be harmed when the chatbot recommends that a consumer buy a more floral blouse that is on sale. If, on the other hand, the DMV replaces their employees with kiosks to reduce customer wait time, overzealous teens may be able to procure a driver’s license illegally and imperil Boulder’s backstreets (among other, more serious risks). The implicated question becomes: what is the threshold for consumers to use and trust a system that they know has been finetuned according to the preferences of a machine? How much risk are people willing to take with Gen AI systems that have been annotated only via algorithms? Roughly 47% of Americans use LLMs, and most use it as a black box, unfamiliar with the underlying methods of how it was trained. It therefore seems likely that many users will the accept increasingly non-human preferences for RLHF finetuning for low-stakes Gen AI uses cases, even if they know that no humans were used in the making of it, since they already (mostly blindly) accept RLHF outputs today. Further research is required to understand the limits of this trust beyond everyday ChatGPT/Claude/Gemini use.

How do we get RLHF to reflect changing societal values?

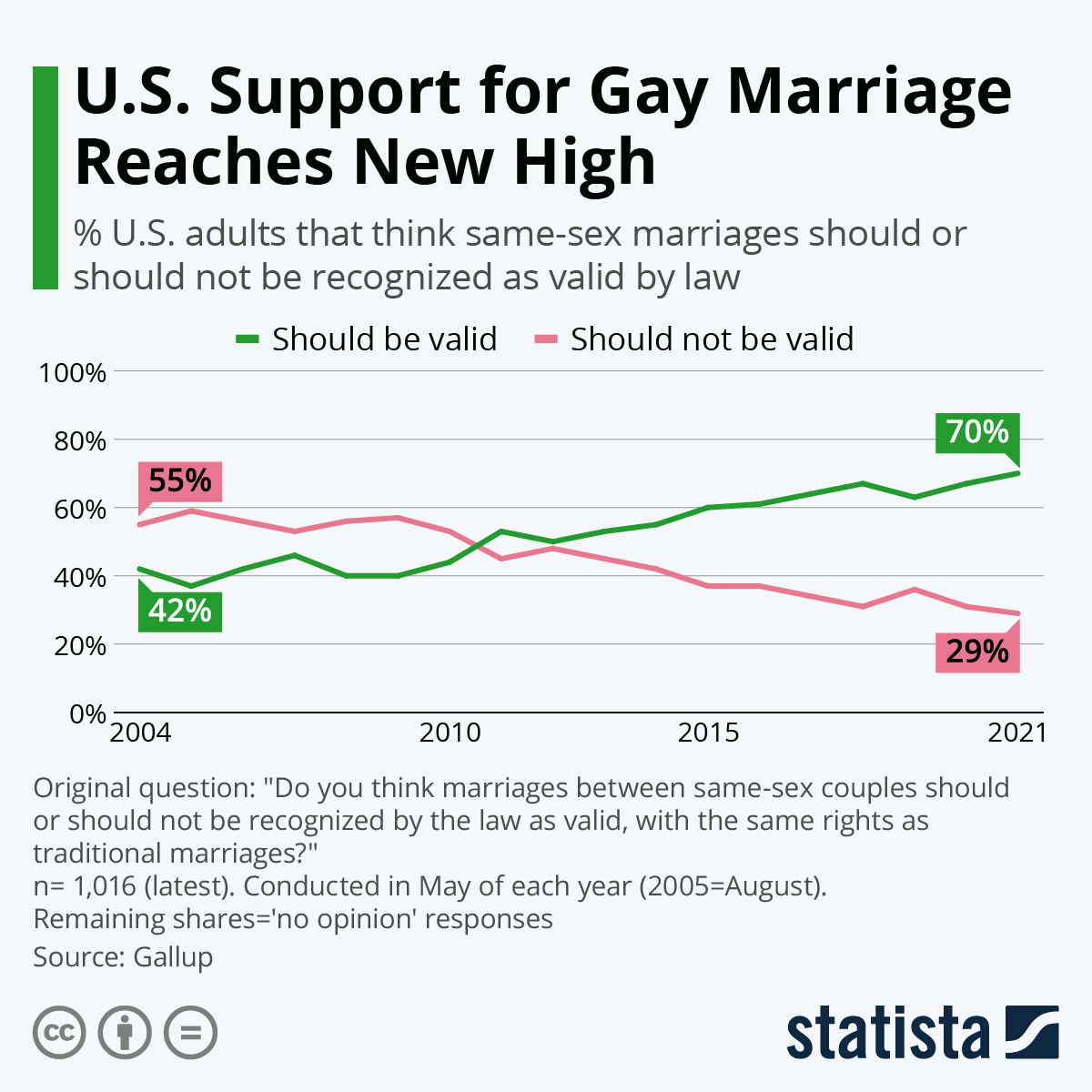

In the US, for example, most people were against legalizing gay marriage in 2009, but by 2011, most people supported it.

This distinct shift in opinion should be reflected in our Gen AI interactions as well. Few would condone a chatbot today who espouses homophobic content. As a society’s values change, so should the RLHF annotations. Updating these too frequently would be costly and superfluous, while clearly waiting too long causes misaligned Gen AI, but what is the best balance between the two extremes? How do scientists know when they need to execute another RLHF cycle? To what extent should the government be involved in regulating this frequency? Would market forces compel the private sector to update their models, even when it costs them additional overhead? Potentially yes, as we saw with the Grok incident, which sparked public outrage and statements from xAI representatives who vowed to remove anti-Semitic content. Does this necessarily portend a whack-a-mole policy, where models are only finetuned after the public uncovers another harmful response?

A larger challenges becomes: how do we model our values as a society? Is it possible to input enough specifics (or are there too many to list?) to fully define the value space, or for generalizations like “do no harm” to fully capture the contours of our beliefs? Right now, the power of Safe RLHF is the number of individual humans that offer inputs that (ideally) represent the population. If the goal is to reduce this human labor, perhaps everyone needs an individual ‘proxy’ LLM that contributes their precise opinions, instead of a single algorithm that is annotating these preferences for an entire batch.

Conclusion

Many exciting directions exist for Safe RLHF methods that increase performance, lower training costs, and more fully represent the desires of the humans who use these systems. By ensuring alignment to our values, we can ensure an experience for everyone that is both helpful and harmless.

References

- Humans in the Loop: The Design of Interactive AI Systems – Stanford HAI

- Grok, Elon Musk’s AI chatbot, started calling itself ‘MechaHitler’ – NPR

- U.S. Support for Gay Marriage Reaches New High – Statista

- Estimating the Usage and Utility of LLMs in the U.S. General Public – Rethink Priorities

- The Story of RLHF: Origins & Motivations – Cameron R. Wolfe (Substack)

- Llama2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models

- Open Problems and Fundamental Limitations of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback

- LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models

- Can Large Language Models Be an Alternative to Human Evaluations?

- Researchers find adding this one simple sentence to prompts makes AI models more reliable – VentureBeat

- Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models

- Pairwise Proximal Policy Optimization: Harnessing Relative Feedback for LLM Alignment

- RLAIF vs. RLHF: Scaling Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback with AI Feedback

- Direct Preference Optimization: Your Language Model is Secretly a Reward Model